Vanishing Appetite

On Ozempic, Soma, and What We’re Really Losing

The developed world is entering the age of less: less hunger, less indulgence, less understanding of food. As a consequence: less conversation, fewer misunderstandings, less laughter, less mess, less random stuff, for better or worse.

At the same time, and ironically, material consumption is booming. Our ‘stuff’ is more and more to be delivered, codified, curated and displayed. Our social lives are lived online, filtered before seen and shared indiscriminately, rather than with people we really want to connect with.

Drugs like Ozempic work by making you stop wanting things. Precisely, food and alcohol. For many, this is a gift. But there’s a cost we’re just starting to talk about—the fading of appetite as a human experience.

Obviously, GLP-1 drugs can be life-changing. The problem is not medical use, but our cultural embrace of appetite suppression as aspiration. We are treating hunger as something to outwit. It’s been like that for the whole of my life - and now, it seems, an easy fix is here.

What happens to a society that no longer wants to eat? When you unwind the economic consequences (let alone the philosophical ones) our whole shared experience becomes a mirage.

Appetite Is More Than Hunger

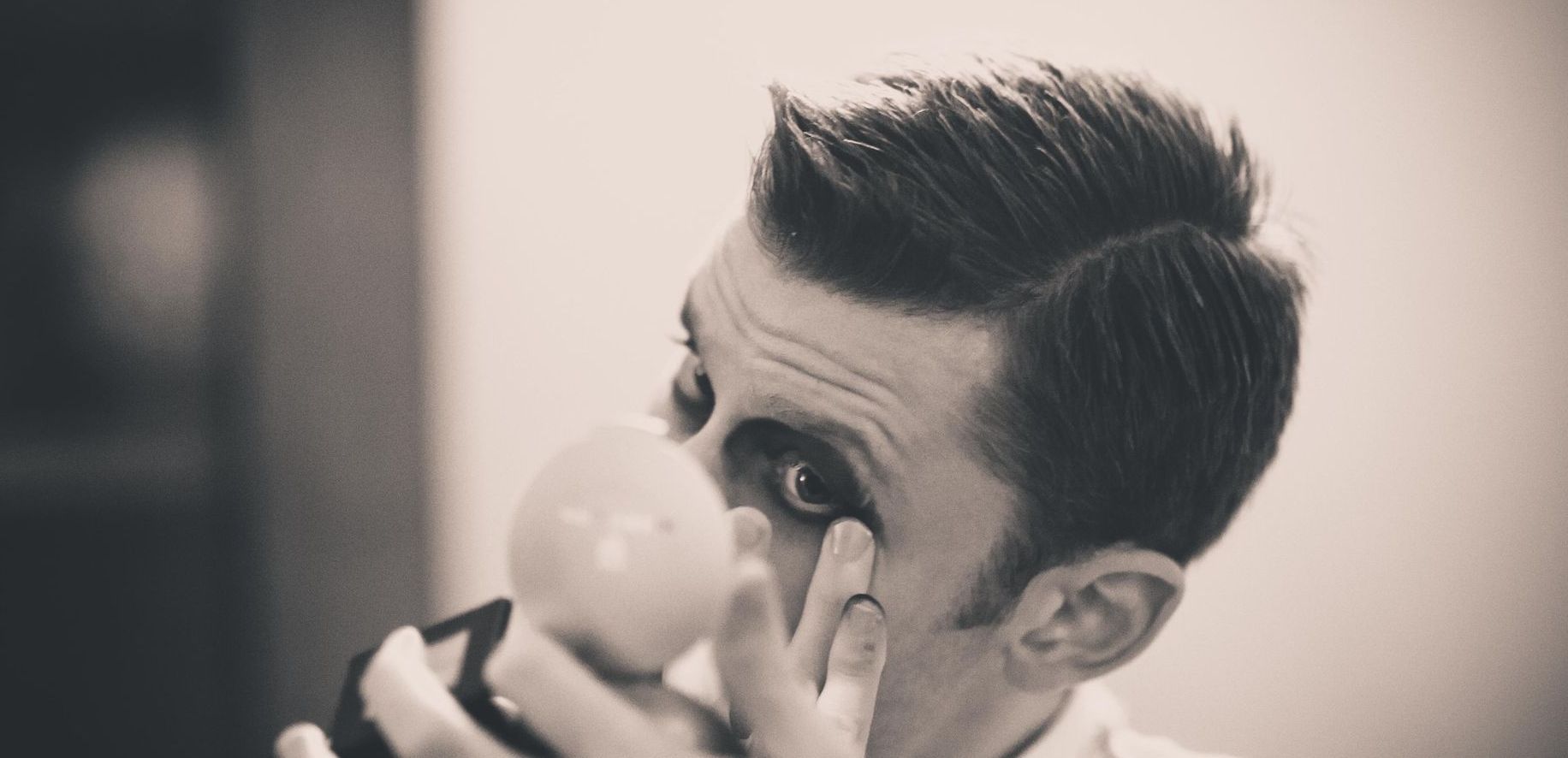

Appetite isn’t just about calories—it’s about longing. The desire to taste, to try, to experience. Appetite drives us not only to the table but toward life, and propels us forward. When you suppress your body’s desires, what else do you cancel?

In the classical world, appetitus wasn’t shameful—it was elemental. The urge to reach, to strive for something just out of grasp is what animates us. To eat well, to drink deeply, to sit at a table with others—this has always been a marker of vitality. Now we are told that to strive for nothing, to cancel wanting, is not only healthy, but virtuous - and gives us status.

A meal is not just food. It is ritual. It is kinship. It is culture. We meet over meals. We reconcile over them. We plan revolutions between bites (or we used to!). Every culture has elaborate customs around shared eating. Even the phrase breaking bread implies a kind of vulnerability—a sharing of the self. Before utensils were commonplace, bread was usually the medium for eating: breaking bread was a communal ceremony to start the meal.

To be unable to eat, rather to no longer wish to, is to step outside the communal circle. You’ve invited the party guest who sips water and eats half a radish. You don’t mind them, exactly. But they change the vibe.

Food writer M.F.K. Fisher said, “Sharing food with another human being is an intimate act that should not be indulged in lightly.” What happens, then, when we no longer indulge in it at all?

The 16th-century essayist Montaigne saw no virtue in excessive restraint. For him, pleasure—eating, drinking, laughing—was something that rooted us in truth. “Le plus grand chose du monde, c’est de savoir être à soi.” (The greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself.) To eat with joy was to possess oneself fully; to share food was to belong more deeply to the world. The dinner table, in his writing, was not a place of guilt, but of trust, companionship, and liberty.

Anthony Bourdain brings this home in a modern sense: “Eat at a local restaurant tonight. Get the cream sauce. Have a cold pint at 4 o’clock in a mostly empty bar. Go somewhere you’ve never been. Listen to someone you think may have nothing in common with you. Order the steak rare. Eat an oyster. Have a negroni. Have two. Be open to a world where you may not understand or agree with the person next to you, but have a drink with them anyway. Eat slowly. Tip your server. Check in on your friends. Check in on yourself. Enjoy the ride.”

A Social Life around Salad (dressing on the side)

Imagine: you’re invited out dinner. You arrive and sit down at the table, but you’re not hungry. You’re never hungry anymore. Your friends order three courses and a bottle of wine, laughing. They talk loudly. They ask for extra bread. You are… patient. Distant. Efficient.

Who are your dinner companions now? Others like you: precise, measured, fasting. Socialising not around sharing, but around discipline. The dinner table becomes an uneasy transaction, not a theatre. You speak less. You go home early. The night shrinks. Throughout our cities, restaurants are closing earlier, people are shutting their front doors (literally) when the sun sets.

And as we eat less, we talk less. Less chance of wandering conversation, chance encounters, arguments about art or politics, or spontaneous plans for after-dinner drinks. The body doesn’t just lose weight—it loses chaos, spontaneity, warmth. And these are things that culture, and connection, often depend on.

Don’t forget: society is a body that needs feeding, as well as your bones and flesh. Think about things that are described in very ‘bodily’ terms: a ‘body’ of work, the ‘body’ politic, a corpus of knowledge….

The Thinness of Virtue

There is something profound about the way Ozempic fits into the modern morality of the body. It offers an illusion of effortlessness. Thinness, without struggle. Virtue, without work. Answers without accountability.

GLP-1 drugs reinforce my generation’s deeply ingrained notion that fat is failure. They allow us to reframe suppression as success.

This is not new. The philosopher Michel Foucault wrote that power often operates by making people discipline themselves—by internalising control. He explored how modern societies maintain power not by force, but by teaching individuals to regulate themselves. “Le pouvoir s’exerce plutôt qu’il ne se possède.” (Power is exercised rather than possessed.). With appetite-suppressing drugs, we may be entering a new phase of that control: the silent body. The obedient body. The empty stomach as an aspirational state. A quiet body = a compliant citizen.

A Hungerless Future

In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley imagined a population pacified by Soma—a drug that dulled pain, quieted rebellion, and produced a pleasant, unthinking contentment. Ozempic is the cousin of Soma. A drug that makes us easier to manage—because we want less. When people want less, they question less. They challenge less. They go home early. Bars and restaurants close their doors.

Maybe the question we should be asking is not how do we eat less, but what are we really hungry for? And what will we all become when the answer is: “nothing at all.”