Past Imperfect

A bite-sized canter through the centuries of trade and colonialism that informed much of the design and personality of Southernhay House. Hang on for the ride:

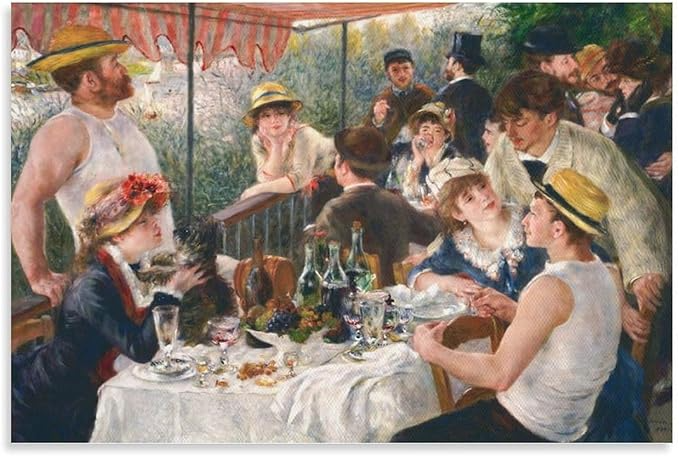

I feel quite protective of my favourite greedy, mercantile, fleshy and feisty Georgians, but it’s fair to say they had few scruples about how cotton, silk, coffee, sugar and tea got into their homes. Worse; if they could make a nice retirement income on a generic trading bond, they would. It built them comfortable country estates and flashy seaside confections all along the south coast.

Southernhay House is the genuine Georgian deal and a central character in Exeter’s history; it’s past and the life of its inhabitants informs everything. The end of the 18th century was a boom time for Exeter. I’m fascinated by this era of new-ness, opportunity, radical thinking, cultural appropriation and worse.

It’s frustratingly hard to get a handle on the extent of the slave trade in Devon because it lies hidden beneath generic investments in “goods” and quiet gentility. But it wasn’t always so: piracy is a first cousin of slaving, and our local Elizabethans were enthusiastic adopters of both. Of course Plymouth and Falmouth, the farthest western ports in England, played a significant part in the transport of goods and people to and from the plantations of the Caribbean and the Americas. It started early, in 1527. William Hawkins, from Plymouth, made a journey to Guinea in a ship named after and funded by the most politically prominent family in Devon. He was after gold, looking for el dorado, but from the deck of the “Pole of Plymouth” William saw Africans loaded for Brazil. In 1562, his son, John, was back in Guinea with human cargo. This is the John Hawkins you will have heard of as being the founder of the “triangle trade”. Public debate about the re-naming of Sir John Hawkins Square in Plymouth is still on-going.

So, to trade. In conceptualising Southernhay House, my goal was to explore, explain and inform you about our Georgian past. The first owner, Captain William Kirkpatrick, was a key player in the East India Company at - if I can use this expression neutrally - it’s inquisitive peak. There was blood, violence and terrible exploitation but there was also an open sense of new horizons, new cultures and discovery.

Naming the rooms became a path to understanding the pathways of European trade, and a way to connect to the modern world. It’s a story that builds, of course, to the worst excesses of Empire. But there is romance and adventure along the way. For those who don’t know your Ambergris from your Opium, here is a bite-sized explanation:

Sericulture is the farming method by which Silk is still produced today - by growing, harvesting and boiling the cocoons of the mulberry silkworm larvae. There’s a word I first learned in 1978, when I heard “Being Boiled” by The Human League - well worth a listen. Silk has been traded since the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD) and is the most ancient of the trade routes, carrying goods between the two then giants, Rome and China. The trade was reciprocal; Silk went west to Rome and wools, gold and silver (from the Roman Empire) went east along a staggered caravan route of over 4,000 miles. You’ll have heard of Marco Polo, who used the route to travel to China (Cathy) in the 13th century to the court of Kublai Khan. It’s quite probable that the Black Death travelled back along the route at the same time.

Spice is a truly global commodity and traded world-wide. The demand grew in modern Europe after Vasco de Gama opened the first ocean route - via the Cape - from Europe to the Indian Ocean in 1489. It was the longest sea-voyage then recorded, taking in the coast of Africa right through to Asia avoided the fish-in-barrel piracy of the Mediterranean. De Gama’s three voyages were peppered with scurvy, ignorance of local faiths, customs and even weather patterns. Pepper and cinnamon were the first spices to hit Europe from Southeast Asia, but soon followed other indigenous products to rapturous demand. Portugal maintained a monopoly over this trade route for the next century. My sense is that, unlike the relative one to one reciprocity of the older Silk Route, this enterprise would have been bloody and crammed with miscomprehension and greed. It would set a precedent for the future empirical aspirations of Holland and England, later France and Denmark.

Tulip is a fun one. So identified now with Holland, tulips were newcomers in mid 16th century Europe when they were introduced from the Ottoman Empire. Who doesn’t love an overblown parrot Tulip? As these flowers became more popular, and demand spread to France, speculators entered the market. Through 1636 the contract price of rare bulbs rose dramatically and suddenly; at its peak a Tulip bulb sold for 10 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman. Forget about the actual flowers; this was the first futures market and the first bubble in one. Contracts to buy bulbs at the end of the 1636 season were bought and sold in taverns at hugely inflated paper prices, buyers paying a 2.5% “wine money” fee per trade but no up-front margin or mark-to-market margin. This was described by many observers as windhandel (“wind trade”). Too right, because, in the expectation of making more and more profit on the trades, the contracts were sold on and on, with some saps hoping to make 10 times or more profit from their “future” Tulip purchases. No surprise, when the enthusiastic wind dropped, the market fell, speculators went bust and sellers were left reaping what they could.

The craze for drinking Chai swept Europe with the English ironically being the last to catch on. When Charles II married Catherine of Braganza, daughter of the King of Portugal, in 1662, she brought with her not only her fashionable tea-drinking habit but also Mumbai and Tangier in her dowry. This gave the British East India Company a permanent base in India, whence they supplied the domestic markets. Chai was initially an exclusive and luxury product. Twinings opened in The Strand in 1706: the cache of tea was strong with Tom Twining. It sold at between 14 and 36 shillings per pound, while coffee went for four shillings. Thomas was also ahead of the curve, and very astute, in opening his doors to women. A Twining actually supplied tea to the Governor of Boston (unknowingly) for his “tea party”. But Chai did not become the universal beverage of England until the end of the 18th century, when duties were slashed (again, a Twining was involved) from 119% to 12.5%.

From the mid 17th century, coffee houses were natural business networks and, taking the lead from Queen Catherine, aspiring aristocratic ladies took to tea. Sugar was their natural bedfellow. The period saw the first planting of cash crops in the new Caribbean “colonies” and the British relationship with sweetness really took off. In an inversion of everything you know, triple-refined white Sugar was the most expensive product, but you could get ordinary brown Sugar at a reasonable price, failing which dark, spoon-standing treacle was the cheapest option. 17th and 18th century recipe books are filled with ideas on how to show off your new habit, from sprinkling Sugar on vegetables to a trifle that’s true to its name. Preserves and jams came into their own. Protectionist policies held import duties low as demand surged, and by 1801 it’s estimated that the English consumed 13.87kg Sugar per person per annum. As of now, it's around 35kg.

Thousands of years of production in India did not mean the Medieval European world was ready for Cotton when first introduced to the fabric. Noting that Cotton is a plant but similar to wool, one author in 1350 sweetly wrote that “there grew in India a wonderful tree which bore tiny lambs on the end of its branches [which are] so pliable that they bend down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungrie.” Those days of innocent, small-scale trading were swept aside by the dominance of British-led industrialised manufacture during and after the Industrial Revolution (the first Cotton mill was built in 1733). Like Sugar, most of the Cotton to feed the mills was grown and harvested by slave labour in the Caribbean and, until the end of the American Civil War in 1865, plantations in America. Between 1825 and 1870, Cotton was Britain’s largest import.

In the 2020 market, Ambergris is half as valuable as gold. It’s been higher. But it’s a good bet that you might not even know what it is, or how to pronounce it. Ambergris (personally, I keep the “s” silent) is an ashy-coloured, rock-like, waxy substance excreted by the sperm whale. It is built up of secretions which the whale uses to avoid lacerations by the small bones and beaks of squid and cuttlefish in its feed. Ambergris has been found for millennia, floating on the sea - and the longer it stays there the better it is cured. Once cured, it smells weirdly divine: in Moby Dick, Herman Melville wrote of the terrible odour of a dead whale, from which "stole a faint stream of perfume". Whales do not have to die for Ambergris to be harvested, but the industrial scale of the whaling industry in the 19th century certainly fed the demand.

There’s one glaring trade that cannot be ignored. You’ve just read about the English beginnings of slaving, so read on for its end. William Wilberforce (1759-1833) is one of my favourite Georgians, albeit a bit of a prude. I admire him for his 18 years in Parliament, continuously lobbying and introducing motions for the abolition of slavery. In 1807, this finally happen to a standing ovation, but the Act did not free those who were already slaves (in fact, Haiti was the first country to abolish slavery in one blow; the European nations all took this two-tier approach). Wilberforce’s work was not, then, done. He continued to lobby until 1833, when an Act was passed to give freedom to all then counted as slaves in the British Empire. Wilberforce died one month later.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the British East India Company bought Opium from Indian producers to sell on the black market into China as a trade for luxury goods such as tea and silk. The British problem was that the Chinese would not buy British products in return for the valued Chinese imports. The Chinese (reasonably) would only sell against universal silver. To avoid depleting British silver stocks, the East India Company - and others - actually began to smuggle Opium from India into China and sell on the black market for silver. By 1839, illegal Opium sales into China paid for the entire tea trade back to Britain. It was a weirdly 21st century horror; although Opium was valued as a medication that could ease pain, assist sleep and reduce stress - by 1840 there were millions of addicts in China. By the time of the final Opium War, in 1860, there was no going back in Anglo-Sino relations: Hong Kong had been ceded to Britain (1842), the prestige of the Qing Dynasty bombed and millions of people had been killed or damaged by addiction in the pursuit of tea and silk.

I have no idea why anyone would buy Ivory, but they have and do. It’s such a pretty word, but I can’t believe there weren’t alternative materials for the fans, hairpins, and snuff boxes of Georgian England. The only time Ivory is useful is veneer for piano keys, since it is durable and apparently sweat-wicking: but I would readily take this loss in exchange for an elephant. Yet, despite trading in Ivory being illegal in most countries worldwide, it persists. Piano keys are no longer an excuse, so I asked Google why anyone still buys Ivory. In 2016, WWF partnered with a phychosocial researcher to get to the cultural roots of the desire that still drives this trade. Studies focused on China, the biggest market for elephant (and other) Ivory. It appears that diehard Ivory buyers today are women with higher than average incomes, living in smaller cities. They buy Ivory because it is rare, beautiful, and it’s still a status symbol for them. No big surprises there, then, although there's a grain of hope in that presumably younger, metropolitan Chinese are rejecting Ivory. Meanwhile, around 47 elephants per day are killed for their tusks. Find out more here.

Saffron. At last, a trade in which no one dies. Maybe related to that is the fact that Saffron is a slow-burner of a trade; it didn’t explode into the western world full of new-ness so demand has built gradually. Although now one of the most expensive spices by weight, the Saffron crocus was quite common throughout Europe, including Saffron Walden, where it was naturalised in the fourteenth century and the stamens used extensively as a dye for the burgeoning English wool trade. The crocus is unknown in the wild and is believed to have originated in Iran, then cultivated in the familiar trading arc of Turkey, Greece, Kashmir. The English word comes from the Arabic word Za’faran and Iran is still the world’s largest producer, which means current sanctions are now impacting on its price. Of course, my fashionable and ubiquitous passion for Middle Eastern cookery also has an effect on this market; all trades rely on a buyer.